M. Dayne Aldridge, Sc.D., discovered his fascination with electrical engineering at an early age. As a second grader growing up in a small West Virginia town, he was already drawing detailed pictures of power lines, right down to the transformers. He even created a microphone and amplifier out of Tinker Toys after watching someone perform.

His family nurtured that curiosity throughout his childhood, with his father encouraging the practical side and his mother emphasizing education. His older brother, already an electrical engineer, bought him a radio kit for Christmas; together they built the kits, allowing them to receive shortwave radio signals. At only 15 years old, Aldridge became a federally licensed amateur radio operator, also known as a “ham” radio operator. “That course coalesced into my wanting to go to college to become an electrical engineer,” he recalled. Aldridge followed that path, earning a bachelor’s degree from West Virginia University (WVU), achieving his goal of working at NASA, his dream being to work in deep space communication.

Innovating space and Earth communication

At NASA, Aldridge worked on a team researching methods to minimize Apollo’s reentry “blackout” time — an eight-minute window when the air becomes very hot upon reentry and limits radio signals to Earth. The team explored high-frequency optical communication methods.

While completing his master’s degree at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Aldridge’s supervisor at NASA encouraged him to pursue a doctorate in deep space communication, as they were looking to have someone do research in the field. By the time Aldridge earned his doctorate in 1968, NASA was scaling back its Space Race efforts. Recognizing that academia better suited his growing family’s needs, he soon joined WVU as a professor, hired by Ed Jones, Sr., who became his mentor.

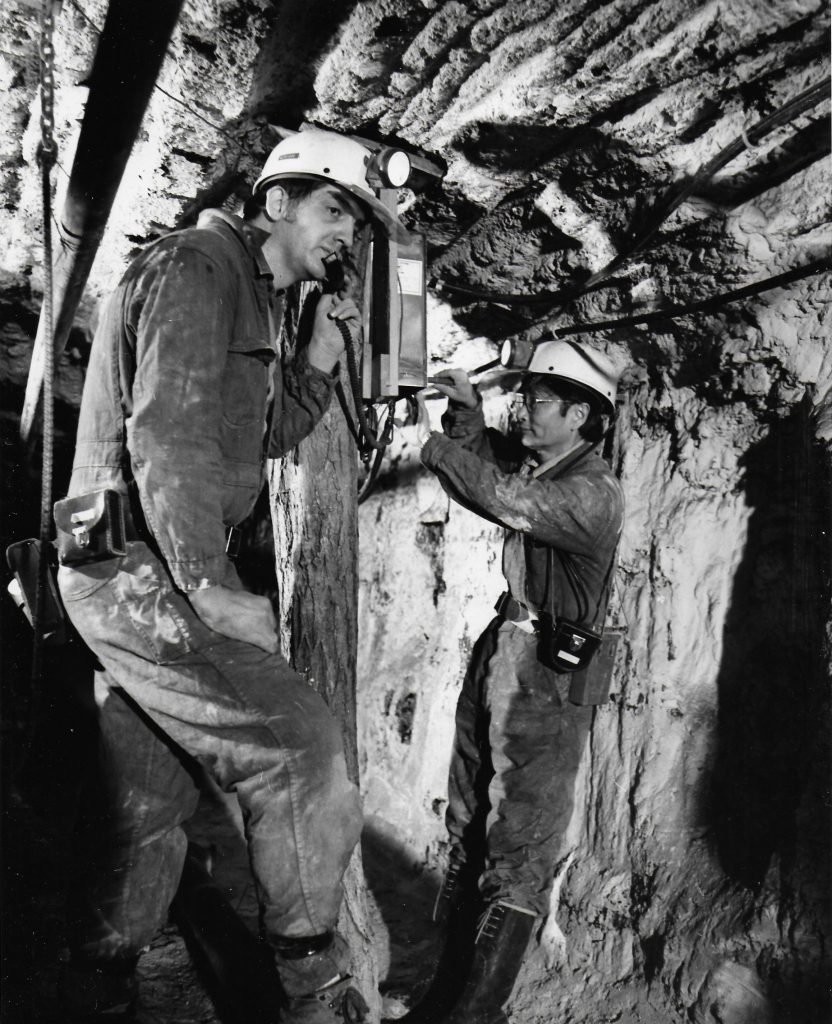

Just months after leaving NASA, the 1968 Farmington, West Virginia mine explosion occurred, trapping almost 100 men underground. This led Aldridge to use his knowledge of coal mining and space telemetry to develop the WVU Coal Mine Monitor System. His team placed about 100 sensors inside an operating coal mine to measure methane gas and airflow to help prevent explosions. “We were developing sensors and demonstrating that you could actually measure these things and monitor them in real time outside of the mine,” Aldridge explained.

The experience gained from the WVU system assisted the commercial development of mine safety systems used today. He went on to be the founding director of what is now the WVU Coal and Energy Research Center and the founding director of the Thomas Walter Center for Technology Management at Auburn University before retiring as dean of engineering at Mercer University in 2008. Despite retiring, he remained active in STEM education quality assurance through ABET, IEEE and the American Society for Engineering Education.

Transforming STEM education with ABET

While serving as an associate dean at Auburn, Aldridge received a call from Ed Jones Jr., the son of his mentor, urging him to become an ABET program evaluator. Although initially skeptical, Aldridge agreed to observe a site visit. “I walked away from the experience saying this was good for both sides and I would enjoy doing this again and being a real program evaluator,” he recalled. He discovered that evaluating institutions allowed him to improve his own program while benefiting those institutions through ABET’s requirements.

Since then, Aldridge has served in multiple capacities as a volunteer expert, including chair of the Engineering Accreditation Commission. He played a critical role in implementing Engineering Criteria 2000 (EC2000), which focuses on student outcomes, or what is learned, rather than what is taught. At its core, EC2000 affirmed the importance of institutions establishing clear objectives and assessment processes to ensure that each program provides graduates with the technical and professional skills employers demand.

In addition to shaping the new criteria, Aldridge helped to establish faculty trainings to guide programs through the transition. Those early workshops that Aldridge developed laid the groundwork for the Self Study Development Workshops offered annually at the ABET Symposium.

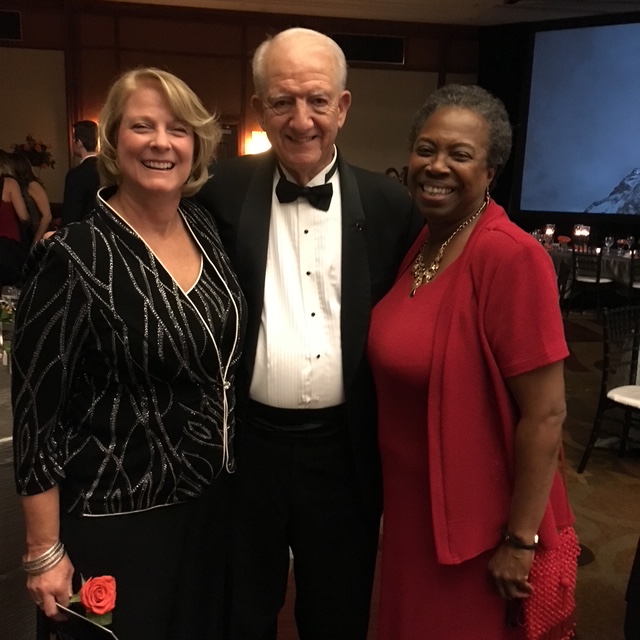

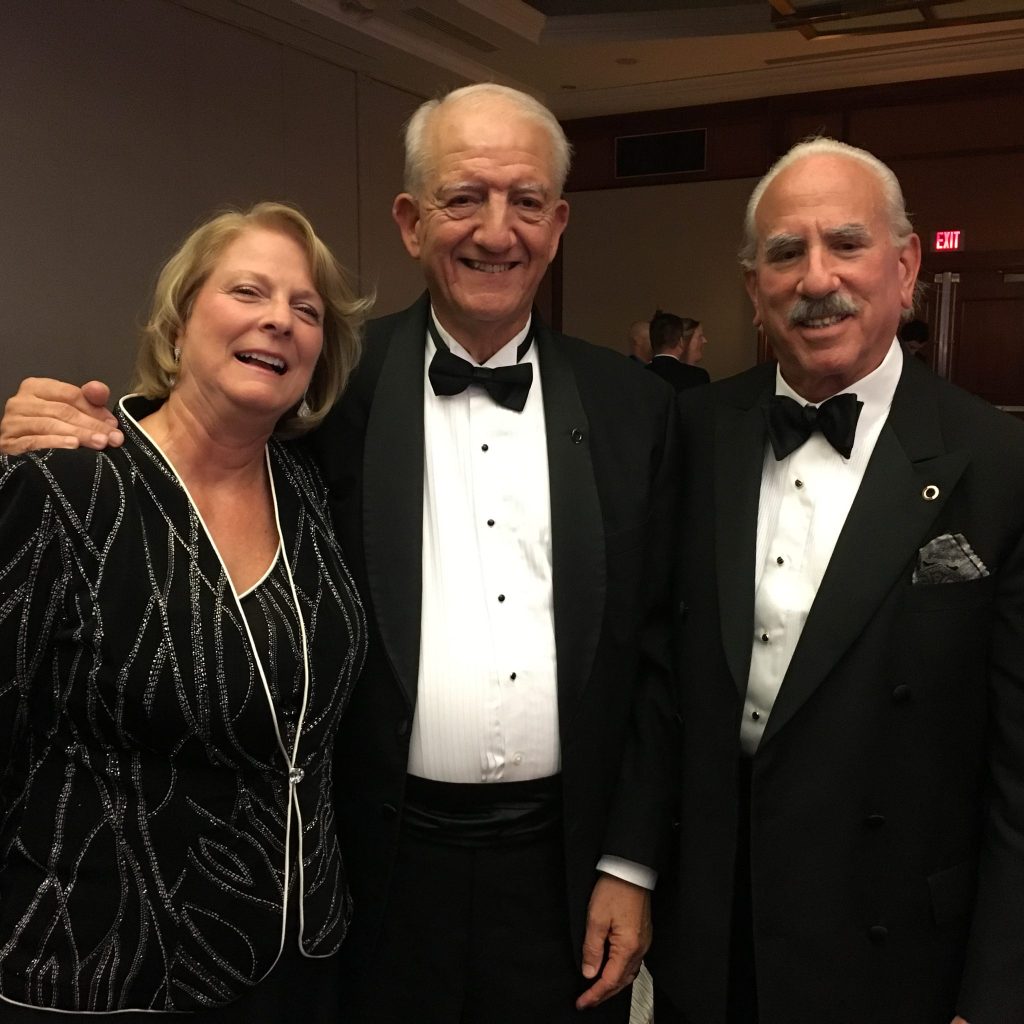

Aldridge received the Linton E. Grinter Distinguished Service Award, ABET’s highest honor, in 2016 for his work on EC2000 and the subsequent faculty trainings. “I feel that ABET is an organization where, for a volunteer especially, you can make a difference,” Aldridge explained. “And it’s a very positive difference.”

Since 2001, Aldridge has served as adjunct director of engineering, where he reviews accreditation reports for clarity and accuracy. “All we can do is recommend. And the leadership and the people who are volunteers make the decisions within the commissions. So, the final decision is made by the volunteers, not by the adjuncts,” he explained regarding the decisions made on accreditation cycles.

Though his role has evolved over the years at ABET, Aldridge’s commitment to future generations of students remains steadfast. “I feel just blessed to be able to have not only been a part of helping that happen but being able to watch it and protect it for the past how many ever years,” Aldridge reminisced. Looking back on his career, he is most proud of his accomplishments at ABET, knowing that he has been a part of shaping STEM education for the better.

Focusing on what’s most important

After a long and accomplished career, Aldridge is quick to point out what matters most to him. “You reach an age where you realize that your professional accomplishments are important but aren’t the most important things in life,” he reflected. While he is proud of his work with ABET and beyond, his greatest source of joy and pride comes from his family.

Aldridge and his wife have built a strong family legacy, raising two sons who, in turn, have given them seven grandchildren and a growing number of great-grandchildren. Most recently, he experienced the thrill of watching his first great-grandson take his first steps virtually, through video.

Aldridge is still active as a ham radio operator with his original call K8CHY, improving his set up over the years to the newest digital technology. “And when you use this method, you don’t hear the noise and the scratching,” he explained. “When you get the signal, it’s very perfectly clear, and it sounds like the person’s right there in the room with you.” With his radio, Aldridge can reach people halfway around the world — not quite all the way around, he quipped.

For Aldridge, success is measured not just in professional milestones but in the relationships he has built along the way. Whether through his contributions to ABET or the time spent with loved ones, his legacy is one of dedication, connection and impact that will continue for generations.